This Age-Old Killer Is Spreading Fast, Why Super Typhoid Isn’t Just A ‘Poor Country’ Problem Anymore

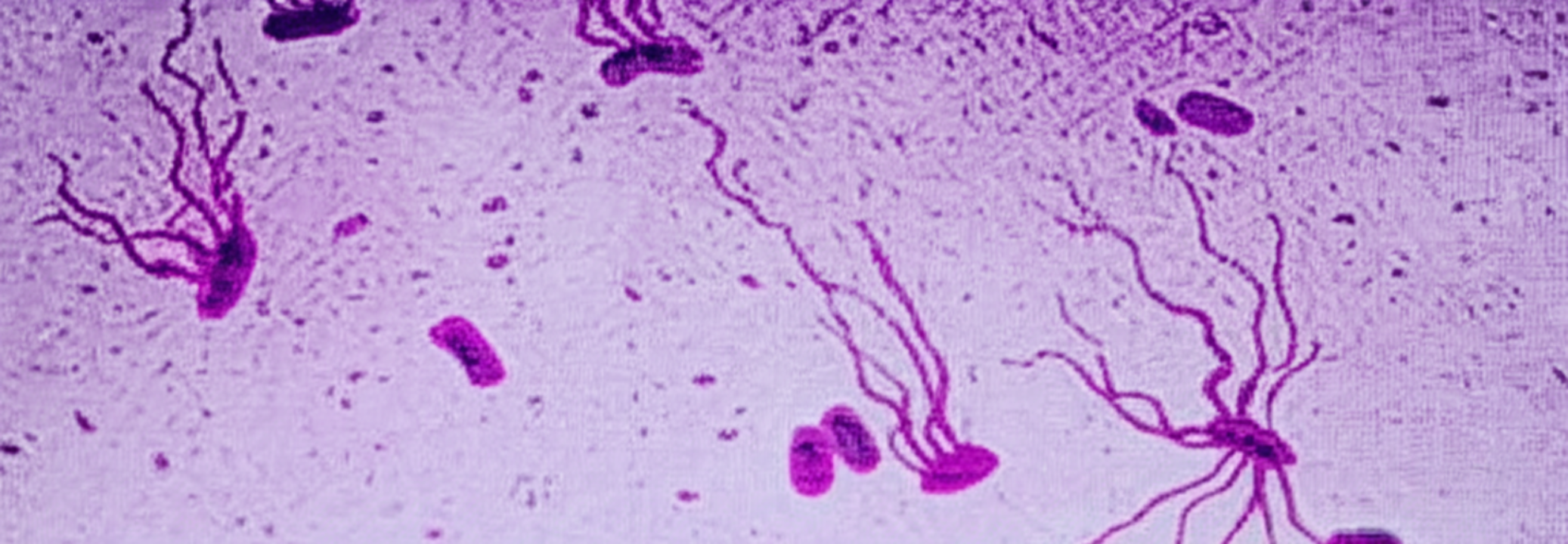

Representational

SummaryDrug-resistant typhoid is rapidly spreading worldwide, with mutations now threatening the last effective oral antibiotic, raising urgent calls for global vaccine rollout and new antibiotic development.

End of Article